|

| Program designed by Jenny Davis |

On February 2, 2016 the Grolier Club and Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library partnered to present a colloquium in connection with my exhibition Blooks: The Art of Books That Aren't. The colloquium was filmed and can be seen in its entirety by clicking on this link: https://vimeo.com/158427834

Speakers included (in this order) Mindell Dubansky (Preservation Librarian, Metropolitan Museum of Art), Lynn Festa (Associate Professor of English, Rutgers University), and Bruce and Lynn Heckman (collectors). Karla Nielsen of Columbia University, was moderator. This post includes the full content of Lynn Festa's inspiring talk on the relationship between books and blooks. I found it so interesting, I thought you would like to reading it and I thank Lynn for offering it to the About Blooks blog:

I want to talk today

both about “blooks” themselves, and about what “book-look objects” have to tell

us about the nature of the book: its properties as a material thing as well as

word-based text. What do “blooks” borrow from the book, on the one hand, and

what do they tell us about the nature of the book, on the other? Why choose to

fashion an object— whether a spruce-gum box, a sewing kit, a lunch box, or a

lighter— in the form of a book in the first place? Although objects shaped like other things are

not all that uncommon—chocolates and

candles and soaps come in all sorts of guises— the blook seems special.

In part, blooks are

special because books are not like

other things: they are both physical object and text, conjoining the material

and the immaterial, the shared world of language and the private world of thought,

sense, experience. Books are strange objects in that they recede into

invisibility when we read; the "blook" by contrast insists upon the

physical properties of the book in a way that makes its materiality an object

of contemplation. “Blooks” remind us of the power incarnated in the book’s— the

codex’s— very form, underscoring the ritual or social purposes that books

possess apart from being read. The

coffee-table book broadcasts a message about the status or refinement of its

possessor without being cracked; the book given as a high school prize declares

an honor without necessarily being devoured by its teen-aged recipient.

Blooks also remind

us of the more casual ways we employ books as material objects rather than

reading matter— as doorstops or paperweights, as coasters or barriers to an

unwanted conversation on the subway. That many blooks are closed books— offering the shape and mass of a wordless object— reminds

us that what we treasure in books is not always the allegedly superior value

incarnated in the text. We also love books as

things. The “blook” on these terms offers a revelation about bibliophilia,

about the love we bear towards this

particular copy of a book, as opposed to the story we love, and about the passion

and perversion of book collecting. Even

as the Freudian fetishist’s interest in the shoe lies in something other than

its purpose as a protection for feet, so too does the collector of books (as

well as, perhaps, the collector of blooks) treasure something that goes beyond

the so-called “proper” use of the book as a delivery system for language. Perhaps— countermanding the chiding of

countless generations of parents— what matters is not what’s inside, after all? The blook as a representation of the

book— with its lavish or cheap bindings, its ornate lettering or unadorned typeface—remind

us of the forms of value not associated with specifically literary merit that also inhere in the book. And why should

we denigrate these other values? The large number of book-objects that are

bibles, for example, reminds us of the role played by the Bible not just as

scripture, but also as a perdurable object that consolidates relationships or

communities through its presence as a material object— not despite but

precisely because of its obdurate materiality. Blooks— or at least some blooks— capitalize on this.

|

| Holy Bible in stone. American, 19th c. |

And I say some blooks, because blooks, like books,

have genres, moving from the reverent sobriety of a stone-book Bible to the low

comedic value of the mass-produced electric-shock gag gift.

|

| Exploding book, "World's Greatest Jokes by R. U. Laffin." American, Franco-American Novelty Co., New York, mid-20th c. |

Blooks thus alternately consecrate the

book— reaffirm its sanctity— and jest with it— cut its high seriousness

down to size. In the next few minutes, I want to offer readings of three kinds

of “blooks”— three possible ways of thinking about what they tell us about our

relation to books that might be roughly classed as the sentimental or

affective, as utilitarian, and as playful.

(This is by no means exhaustive, and for every statement I make there

will be a counterexample.)

First: the

sentimental or affective. “Blooks" toy with a kind of literalization of

the inward nature of the book and of our reading practices. On these terms, we

might read the book-object as a kind of allegory of reading. The hollowed-out book shape, for example,

literalizes the ways we think of reading as an activity involving depths and

insides: we dive into novels, we delve into texts, we talk about what’s in a book.

|

| "Smoke and Ashes by Flame" smoking set. American, mid-20th c. |

A book repurposed as a secret

hiding place for keepsakes has much to tell us about the forms of interiority

and selfhood we associate with the book. Books, like blooks, offer passage to a

hidden inside. Although not all blooks open,

the pleasure of opening and finding things within— and here I cannot help but

think of the popularity of “unboxing videos” on youtube as a strange extension

of this pleasure— is part of what the blook promises. The discovery that

something is harbored within the blook thus echoes elements of the experience

of reading.

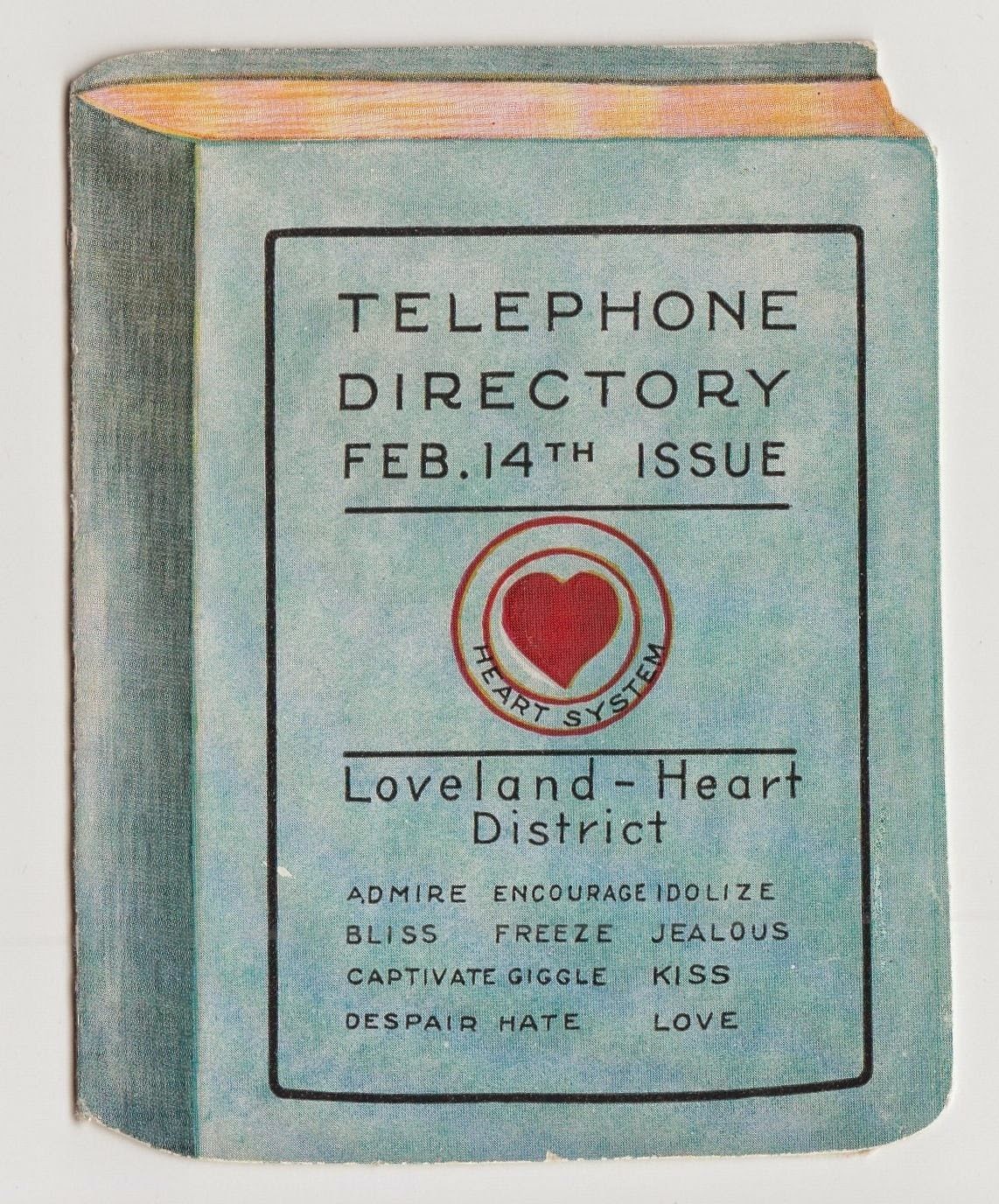

Blooks also

capitalize on the way books, as embodied language, exteriorize and make inner

feeling at least partially available to other minds. The book-shaped love tokens and sentimental

or memorial objects such as the spruce-gum boxes carved by lumbermen in the

North Woods or the stone books carved with the name of the recipient all are

exterior signs of inward emotion.

|

| An American spruce gum box, 19th c. |

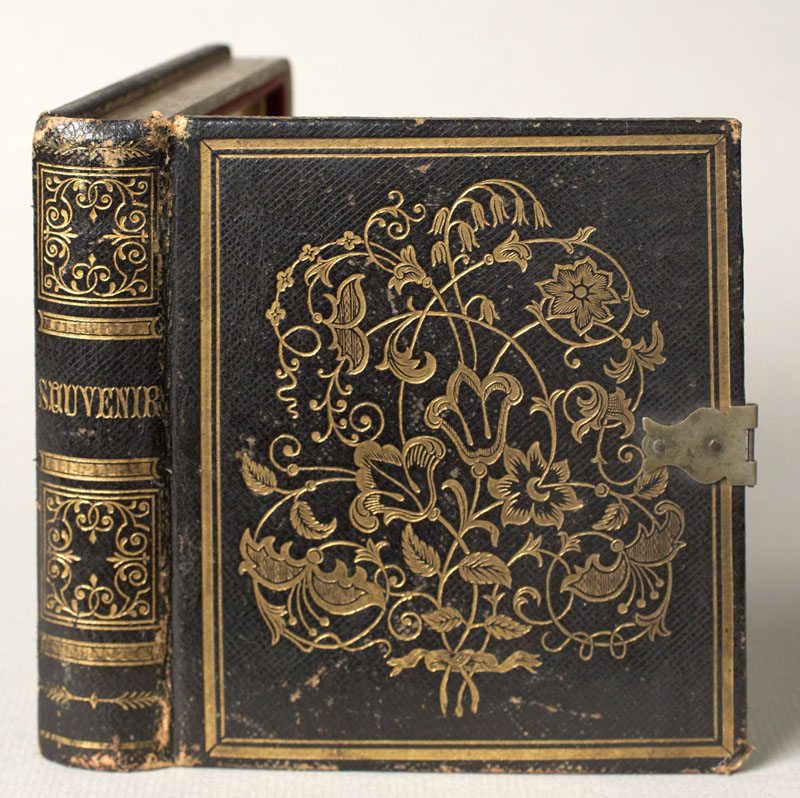

As

personal memento, keepsake, memorial, souvenir, or gift, these objects are vessels

for sentimental value. I want to focus on the anthracite book that commemorates

the death of the miner James Fagen at the age of 22.

|

| Coal memorial book from Pennsylvania, 1897. |

This blook marks the

premature ending of a life with too few chapters. The fact that it can’t be

opened to be read— that it is a closed book in every sense— and the “muteness”

of the stone book— the “inert thingness” of the memorial— make this blook the

nonverbal expression of something— the grief of loss— that cannot,

perhaps, be brought to the level of language. Words cannot express

everything. The stone book that marks

this foreshortened life borrows from the permanence or solidity of stone to

suggest the enduring love towards the lost loved one and the promise of eternal

life, also invoked by the book’s inevitable reference to the bible. The emotion

that suffuses these objects makes the blook, like the book, a tool for

preserving and revivifying emotions about absent objects. Both blooks and books

give substance and form to the ephemerality of subjective feeling, experience,

thought. (One thing that does not come through from looking at the blooks in

the exhibition is the immense pleasure of holding them: the smoothness of the

wood, the texture of the grain the heft of the stone, the satisfying fit, snug

in the hand. These are tactile as well

as visual objects; they are meant to be held.)

If the sentimental

or affective “blooks” serve as objects of meditation or contemplation, what

should we make of their more utilitarian counterparts? What connections can be

made between the contents of certain blooks and the book form? The logic behind

housing writing materials, alphabet blocks, and a book repair kit (charmingly

titled “The Care and Feeding of Books”)

|

| "Care and Feeding of Books" book repair kit. American, mid-20th c. |

in a book-shaped container is fairly

evident, to be sure, and the fact that blooks are often vessels for new or

emerging technologies— photographs, viewfinders, microscopes, cameras, and tape

recorders—suggests the ways the book-form acts as a mediator to buffer

technological change (as in “pages” and “folders” on our computers).

|

| Crosley Book Radio. American, 1950s. |

Some

blooks— the game boards disguised as books, for example— are perhaps trying to

borrow from the relative prestige of the book to give idle pastimes greater

respectability.

|

| Add caption |

|

| "Milton's Poems" card set. American, mid 20th c. |

But other objects are

not so easily explained. One might, I guess, say that the incendiary content of

literature and the flammability of paper explains the book-shaped trench-art lighter

(and certainly the useful object crafted out of shell-casings and bullets

produces a reminder for the soldier of the civilized world of books, so distant

from the violence of war), but what about the sewing kit? Why put a sewing kit like the 1840s “the Gem”

in a book form?

|

| "The Gem" small sewing kit. English, 1840s. |

Although part of the reason is decorative (a pretty, fashionable

case, easy to transport), another reason is perhaps to hide or camouflage the

object. A sewing kit in a book form allows work materials to be left out on a

table, and thus ready-to-hand for the kinds of minor repairs for which it is

intended, even as the book form disguises the invisible ubiquity of female

labor that underwrites domestic life. Perhaps the practical contents of these blooks

also serve as a reminder that “book smarts” need to be complemented with

practical know-how: the speculative “how-to” knowledge that reading a book about

tailoring might convey is replaced by the sewing-kit that enables one to mend a

shirt.

Although the sewing

kit blook disguises its contents, many blooks do, punningly, proclaim what they

ostensibly hide. The flask is nestled in

a blook labeled the Secrets of the

American Cup,

|

| "Secrets of the American Cup" flask. American, 20th c. |

while the clothing brush is housed in Not So Dusty by Y.B. Untidy.

Here the blook form has recourse to language— to words— to suture the

relation between the book form and the blooks’ contents.

|

| "Not So Dusty by Y. B. Untidy" clothes brush. American or English, 20th c. |

That so many blooks have punning titles is, I

think, a reflection of the fact that there is something oddly literalizing

about the blook. It arrests us on the material form of the book in much the

same way that the pun returns language to its most material form, as

sound. The pun plays with the sonic

similitude of words, much as the blook plays with the material likeness of the

book.

The importance of

puns indicates that all is not high seriousness in the world of blooks, and I

want to close with a few words about the sheer entertainment value and even

silliness of some blooks. The gag books in the exhibition— the folk-art trick

snake boxes from which a snake rises to strike the unwary Pandora,

|

| Snake trick. American, 19th c. |

the

exploding books and the electric shock books— all entail a curious

materialization of reading: the serpent serves as a reminder that dangerous

things lie in books, while the shocks inflicted in opening a risqué cover literalize

the notion that we are reading something “very shocking” (offering a playfully

punitive response to the prurient desires that led one to open the book in the

first place). These blooks sport with the pleasure of being surprised or

perhaps, rather, with the pleasure of surprising someone else (the vague sadism

of many practical jokes). But they also play with the delight at illusionistic

trickery associated with trompe l’oeil, with the outward mimicry of a form that

turns out to be something else. Wherein lies the pleasure of being lured into

seeing a book in an object that is not

a book? I think the pleasure— and the profit—elicited by this fleeting mistake lies

in the toggle between one thing and another that alerts us to the enduring

relation we take to books. For in not

being a book, the book-look object offers us a glimpse of the many things that

we ask books to be.

Dw~~60_57.JPG)